Ph.D Portfolio

impulse|resonance

In resonance the inexhaustible return of eternity is played—and listened to.

Jean-Luc Nancy – Listening (2007)

As a medium that affords manipulation and juxtaposition of sonic events of any kind, electronic and electroacoustic music offer a context for a creative expression of the excluded; marginal sounds and dissident voices. Through decomposition, reprocessing, and recomposition, a material that is denied expression due to its semantic content or aesthetic features can be re-contextualised and re-presented. Iranian literature, music, architecture, art (including craft) is full of such examples. This way of approaching composition does resonate with the practices of experimental electronic music in Iran as well. Although one may criticise such an approach as politically passive, in its disciplined creativity it nevertheless provokes dialogue. Also, in its aesthetic novelty, it allows easier negotiation with the political system, in times when the political system may be too intolerant of the nation’s direct critical expressions. The central element of this piece is a cell produced of two samples extracted from two songs with Persian lyrics. The first sample involves the word ‘Iran’, which is isolated from a song titled Baroon Miad (Persian: بارون میاد), meaning ‘rain is falling’, produced by Fedai Guerillas in 1970s. The second sample involves the Persian word man (Persian: من), meaning ‘self’ in the context of the song. It is extracted from a rap song titled Kavir (Persian: کویر) meaning ‘desert’ by Ali Sorena , produced in 2017. Both samples are, however, processed in such a way that their semantic contents are concealed.

ecbatan

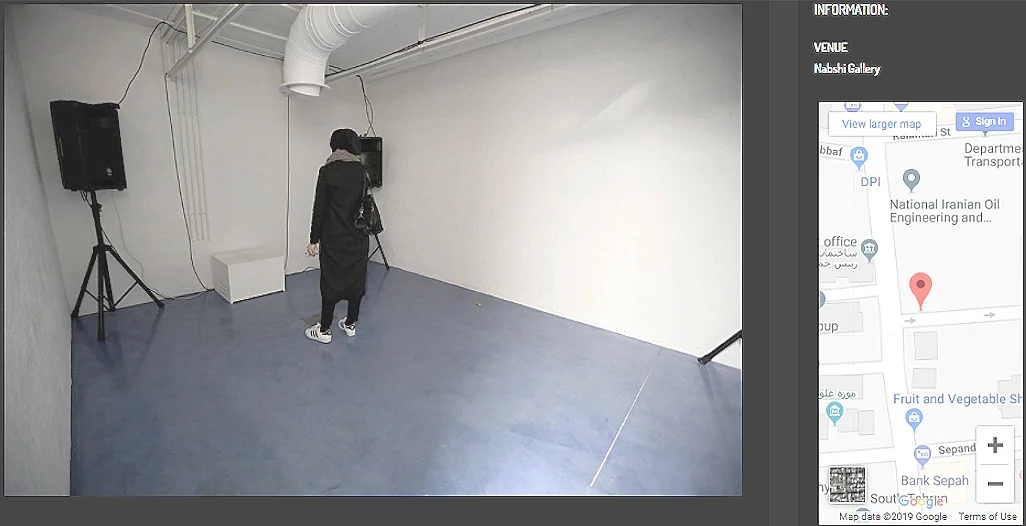

ecbatan is a 6-channel sound (speakers and transducers) and material (plywood) installation. It was exhibited as a 4-channel sound installation at TADAEX 2018 in Tehran, Iran.

The piece is formed around one guitar arpeggio. I had first used this arpeggio about fourteen years ago (in 2005), during a White Comedy recording at Kargadan studio in Tehran. It was discarded from the album’s final mix. For the purposes of ecbatan, I retrieved it from a recording that had been made during one of the bands’ jam sessions at Kargadan. Working with this material, recycled from an old archive of discarded recordings, I sought to somewhat reinstate a spatial and material connection with an environment to which I had lost physical access. Viewed in the context of broader trajectory of my practice during the course of this research, ecbatan is a pivotal piece as it marked the beginning of a transition between two different approaches to composition: a familiar one according to which pieces were carefully planned and written and an emerging one that tended towards more performativity and was open to accidents. In my earlier works one of the main concerns was to figure out ways of exercising precise control over sounds and their spatial manifestations within a piece, in order to make them subservient to my compositional needs and aims. In my later works, however, these concerns increasingly shifted towards finding creative ways of giving up the precise control through more spontaneous and performative approaches to composition that involved improvisation. In The Lived Experience of Improvisation (2017) Simon Rose notes: ‘The immediacy required for composing in the process of performing calls for a particular presence in time within engagement in the world, an intervolving.’ (161) Through a retrospective reflection I would note that composing in and through performing became a focus, perhaps because it increasingly felt relevant to the new conditions of my life as I transitioned between the two societies (Iran and UK). This change took place organically and through an ongoing exchange with the practice of my interlocutors and that of my colleagues and friends in the UK, especially in SARC, where I have been based since summer of 2014. In this context, ecbatan can be viewed as the sonic/musical articulation of such a transition as well; one that marked the flow of time and embodied an experience of place and a mode of becoming—transitioning between a state of being refugee to a state of becoming permanent resident (and then citizen); from a state of insecurity and float to a state of relative stability and ‘grounding’.

Ornamental descend

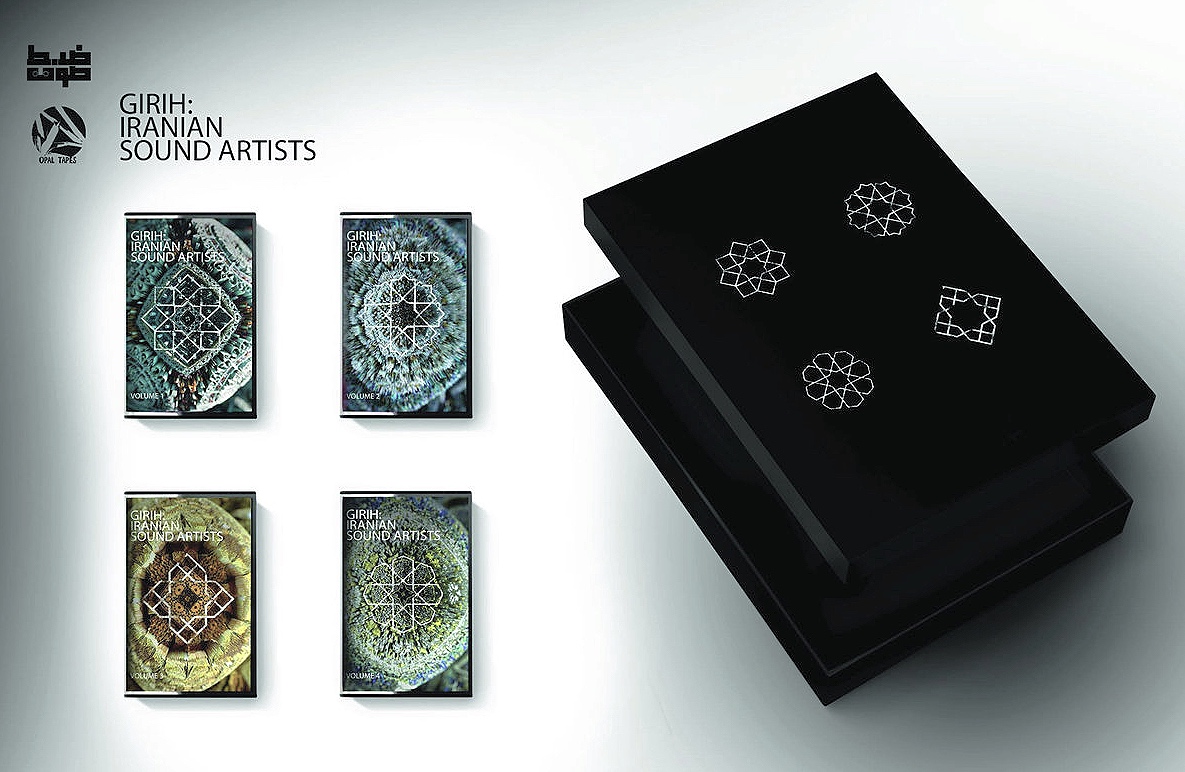

The main idea of ornamental descend was to respond to Ata Ebtekar’s practice. Ata’s work has provided a predominantly ambient scene with an important nuance and, as such, encouraging the development of new styles. Having uniquely, and rather confidently, engaged with elements of Iranian classical and folk music, his repertoire of practice provides a significant contrast to that developed by his former colleagues in SET (especially in early years). His work somehow bridges elements of ‘sophisticated’ club music—closer to forms such as idm and breakcore—and electroacoustic music. In an environment in which many forms of music typically played in clubs are not allowed to be represented in public in any shape or form—the kinds one may generally call, regardless of their different genric characteristics, ‘groovy’ or danceable—Ata’s practice fills an important gap. It is partly thanks to Ata’s music, optimism, enthusiastic conduct, connections, and PR abilities that SET has grown to such an extent, becoming the number one platform for experimental electronic music in Iran with a reputation that goes beyond the country’s geopolitical borders.

Ornamental descend is 04:03 long and, as such, is my shortest composition within the portfolio. It is composed based on a ‘musical’ phrase that appears at 02:31 and gradually develops through different variations and ornamental passages until the end of the piece. It explores microtonal structures, particularly quarter-tones, in a ‘pop’ music context—due to its length and riff-oriented character—similar to the majority of Ata’s works. All sounds are formed through performing with Eurorack modules—a wavetable synthesizer, oscillators, filters, lfos, sequencers, and envelope generators. To achieve the kind of microtonal intervals and ornamental passages that the work involves, different couplings of control signals and audio sources were explored. The piece’s main sonic cell—the phrase that appears at 02:31—is developed throughout the piece in the form of call and response, which is a common compositional technique in dastgāh music (a modal system used in Iranian classical music). Developed ornamental passages have been considered as virtue of a skilful performer within Iranian folk and classical music for centuries. Performers of Iranian ‘traditional’ instruments have been recognised and praised within Iranian classical music literature for their authentic and elaborate use of ornamental passages. Quarter-tones are also contained in many Persian dastgāhs, and, as such, are known as one of the characteristic sounds of Iranian folk and classical repertoire.

pendulum

[There is] no point of stability or centre [with regards to our cognitive relationship to the perception of music, and to the larger world]. As in a vibrating string, the axis of the oscillations performed is the string at rest. Such a middle ground would be tantamount to silence. Resonance, by contrast, requires oscillation of both the mind and the ear. It summons us to always keep on percussing, discussing, percussing.

Veit Erlmann – Reason and Resonance (2014)

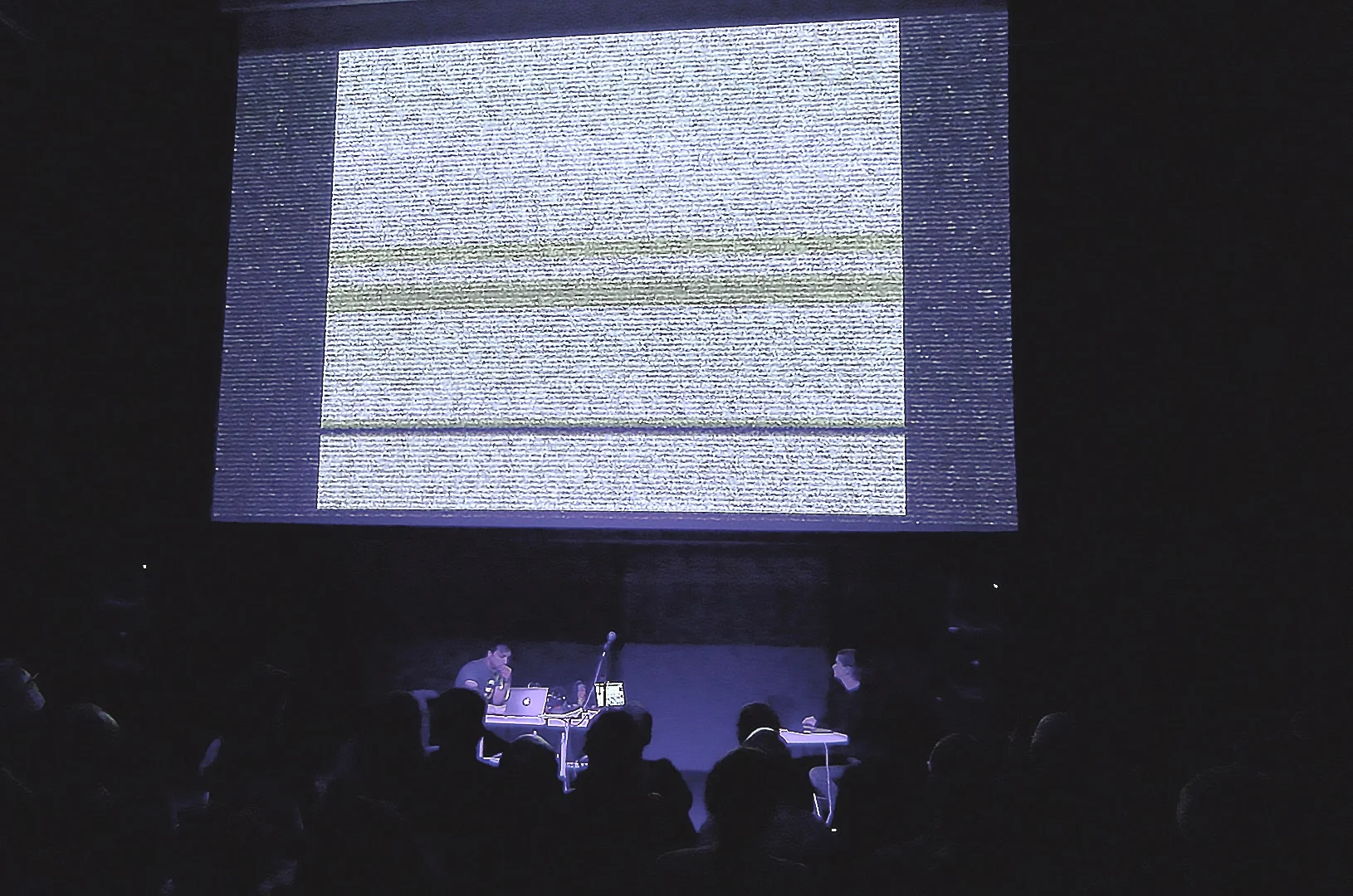

pendulum us an improvised live electronics and visuals performance, created in collaboration with Steph Horak. It was presented at Sonorities festival 2018 at the Sonic Lab of the Sonic Arts Research Centre, Queen's University Belfast.

The main idea for the piece is, on the one hand, to explore, based on our own texts and sound-based practice, the apparently ‘instinctive’ human tendency towards constructing dichotomies in dealing with complex issues. We had conjectured that the existence of such a seemingly ‘natural’ inclination is a basis for the emergence of many forms of technology including the digital. To that aim, we surveyed various uses of binary oppositions within our own poetic and reflexive writings and picked a number of texts, which reflected those in relation to the notion of ‘difference’ with regards to issues of identity, gender, race, culture, and politics. On the other hand, we were keen to reflect on digital music media’s capacity to ‘reopen creative agency’ (Born 2005, 26) through ‘decomposing’ the ‘aural and visual objects into basic binary representations’ (ibid, 28); an underlying driving force responsible for the emergence and burgeoning of a digital arts and experimental electronic music scene in Iran that has been subject to scrutiny in this text. In this context, pendulum’s aim from my perspective was also to respond to a relatively recent, and still very niche, interest within EEMSI in relation to live improvised electronic music performances; a form which has been almost completely absent from the scene’s live repertoire.

intra.view

This piece was presented in collaboration with Anna Weisling (on visuals) at Sonorities Festival 2018 in the Sonic Lab of the Sonic Arts Research Centre (SARC), Queen's University Belfast. The composition was created in response to a musical dialogue with Kiana Tajammol, Sohrab Motabar, Ramin Safavi, and Mo H Zarrei.

Steven Feld had previously argued that ‘art-making is something that could be and should be central to anthropological thinking […] [although] it has never happened.’ (Feld in interview with Angus Carlyle, in Lane and Carlyle 2013, 207–211) Feld’s Jazz Cosmopolitanism in Accra (2012), which reports on his experience of performing and recording with the Ghanaian musicians, could, however, be viewed as an example where this synthesis had happened. Inspired by Feld’s work and Simon Waters’ paper Tullis Rennie's Muscle Memory: Listening to the Act of Listening, I set out to explore how this research could benefit from collaboration. Considering the fact that I did not have physical access to the ‘field’ and that I had to mainly rely on online ethnography and my own experiences, also on my broader research and sound-based practice of course, this experiment could potentially contribute significantly to this PhD, and so it did. The idea was to investigate how collaborative composition could be exploited simultaneously as ethnography and instigative-artistic practice for a more engaged and less-mediated exploration of the music scene in Iran.

Slides-zen-Dives

The idea of this piece took shape when Kate Carr asked me on Facebook if I was interested in performing as part of an electronic music event that she was curating at IKLECTIK Art Lab in London. I have known Kate in person since 2016. I first found out about her involvement with EEMSI following the release of Birds of a Feather; an album by the Sanandaj-based field recordist and sound artist Porya Hatami and the Toronto-based producer and sound artist Michael Trommer. It was released through Kate’s own record label, Flaming Pines, in 2012.

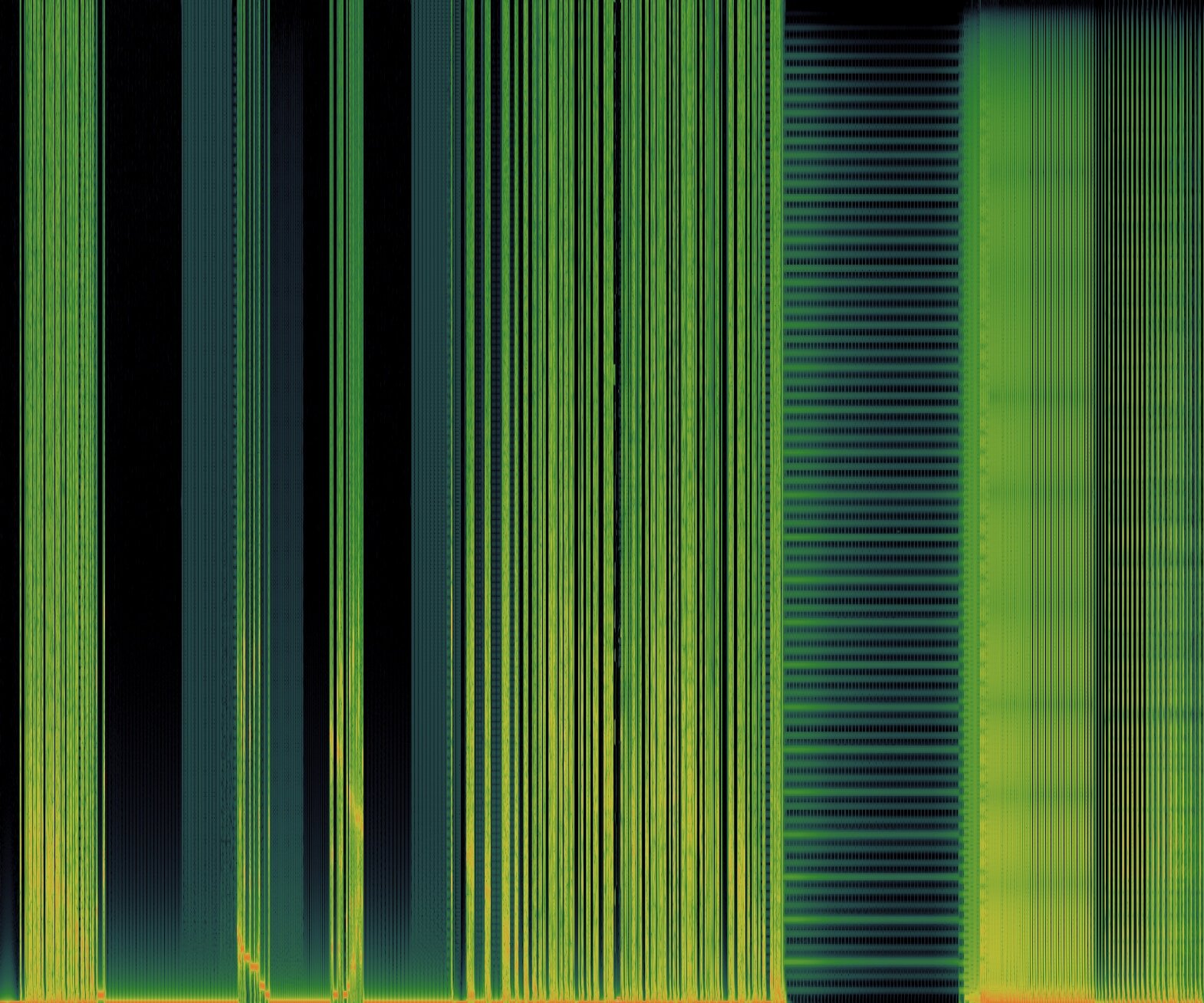

The set developed, spontaneously and organically, as a series of drone parts and a percussive passage. The sonic output can be described in terms of constantly moving clusters of electronically-generated glissandi of different kinds that interweave and complement each other while heading towards nowhere specific. To add more layers of ‘liveness’, two contact microphones were used on my modular system’s case during the show, which allowed me to amplify, further process, and play with the often undesired and supressed ‘noises’ resulting from physical contact between various parts of the system and my hands. These can be heard at the beginning of the recording as I start patching, for instance between 00:34 and 02:58, and towards the end as I begin unpatching to restore the system to its initial state, for instance between 13:27 and 15:10. I wanted to start the set with no prepatching, to return to a similar state in the end and, as such, to begin and end with the ‘noise’ of the ‘background’ and the patching process, while integrating, instead of trying to eliminate or supress, the usually unwanted sounds of the environment and of the performance ecosystem.

spin

The composition process began with a survey. An online questionnaire was sent to twenty electronic producers based in Iran, who were chosen at random. Participants only had to open the link of the online survey, fill in the form anonymously, and press submit. Within the form everyone was asked to respond to the following eight questions: 1- How long is your average daily usage of the internet? 2- For what purposes do you mostly use the internet? 3- What sound sources do you frequently draw from in your practice and how do you access those 4- What soft-ware/hardware are more frequently used in your practice and how did you learn to use those? 5- Have you ever been trained, outside your individual endeavours, to manipulate sound, to compose, and to work with the software/hardware you use in your practice? 6- How do you describe your work in terms of genre aesthetics, if at all? 7- Do you see a connection between using the internet and the development of your practice in any shape or form (explain)?

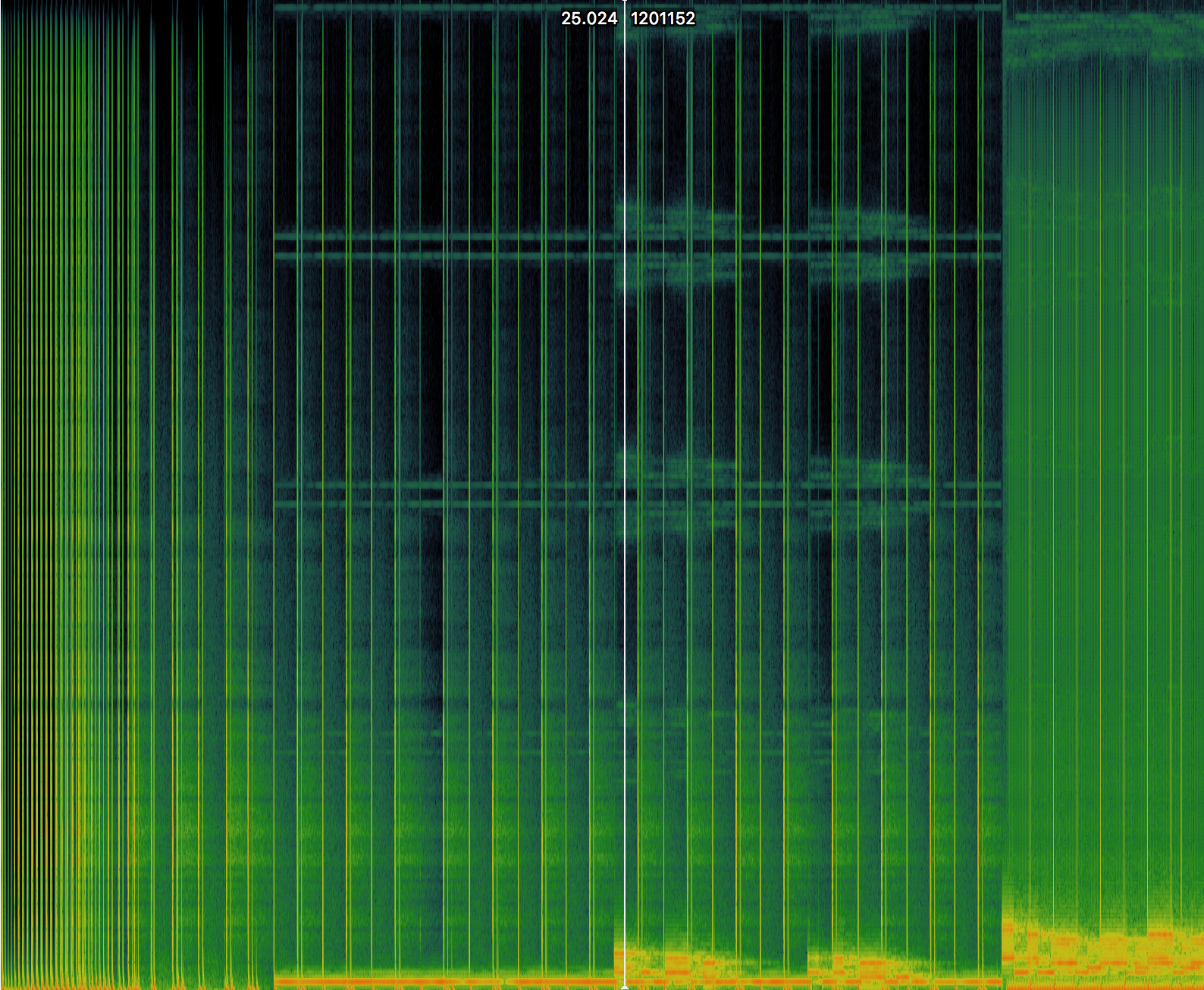

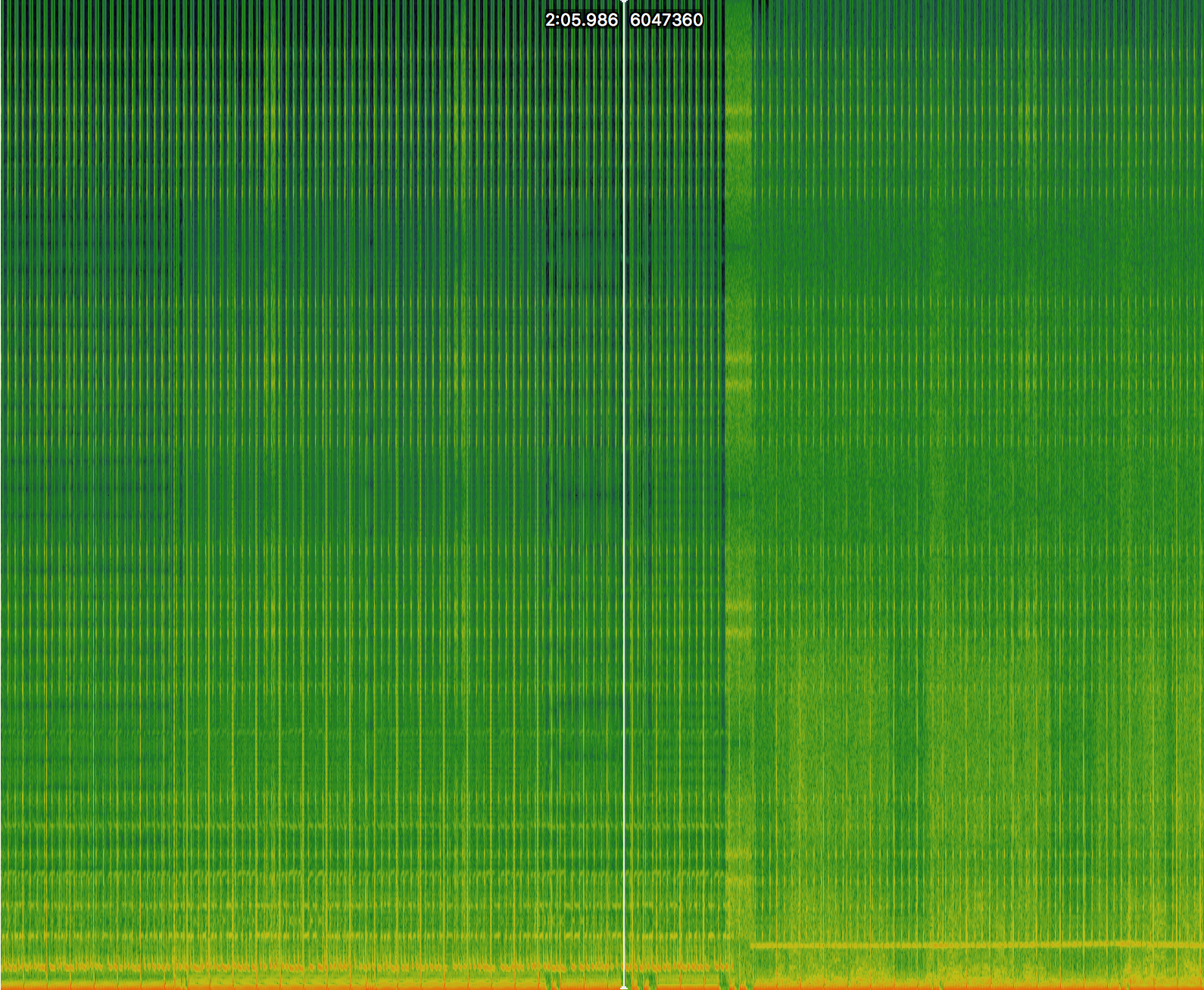

SPIN and INTERFERENCE are composed based on samples contributed by Sohrab Motabar and myself. These two pieces constituted my first attempt to map seemingly unrelated data in the context of medianthropy, through music. To that aim, all samples were randomly selected from a library of recordings that Sohrab and I had shared via Dropbox. Through the latter process a sound library for these two works was formed, which consisted of original recordings as well as samples extracted from two online sources: British Library and BBC archives. In SPIN, for instance, the orchestral string sounds that appear at 01:17 belong to a 1950s vinyl recording and is extracted from the British Library’s page on Soundcloud (unfortunately I cannot find the exact link for the relevant recording). The FM radio tuning sounds that appear at 02:43 belong to an archive of BBC recordings, which was officially released on April of 2018. The rest of the material in this piece are all original recordings. INTERFERENCE is, however, wholly based around five short samples that are introduced successively at the beginning of the piece until 00:12. These were extracted from Sohrab’s samples, which had been generated using code written by himself in SuperCollider . The distorted radiophonic voice that first appears at 01:01 was also extracted from the BBC archive.

interference

The composition process began with a survey. An online questionnaire was sent to twenty electronic producers based in Iran, who were chosen at random. Participants only had to open the link of the online survey, fill in the form anonymously, and press submit. Within the form everyone was asked to respond to the following eight questions: 1- How long is your average daily usage of the internet? 2- For what purposes do you mostly use the internet? 3- What sound sources do you frequently draw from in your practice and how do you access those 4- What soft-ware/hardware are more frequently used in your practice and how did you learn to use those? 5- Have you ever been trained, outside your individual endeavours, to manipulate sound, to compose, and to work with the software/hardware you use in your practice? 6- How do you describe your work in terms of genre aesthetics, if at all? 7- Do you see a connection between using the internet and the development of your practice in any shape or form (explain)?

SPIN and INTERFERENCE are composed in response to the survey answers and based on samples contributed by Sohrab Motabar and myself. These two pieces constituted my first attempt to map seemingly unrelated data in the context of medianthropy, through music. To that aim, all samples were randomly selected from a library of recordings that Sohrab and I had shared via Dropbox. Through the latter process a sound library for these two works was formed, which consisted of original recordings as well as samples extracted from two online sources: British Library and BBC archives. In SPIN, for instance, the orchestral string sounds that appear at 01:17 belong to a 1950s vinyl recording and is extracted from the British Library’s page on Soundcloud (unfortunately I cannot find the exact link for the relevant recording). The FM radio tuning sounds that appear at 02:43 belong to an archive of BBC recordings, which was officially released on April of 2018. The rest of the material in this piece are all original recordings. INTERFERENCE is, however, wholly based around five short samples that are introduced successively at the beginning of the piece until 00:12. These were extracted from Sohrab’s samples, which had been generated using code written by himself in SuperCollider . The distorted radiophonic voice that first appears at 01:01 was also extracted from the BBC archive.